You see a problem at work and you think you have a solution. Some people you have spoken to in hallways agree with you. So you go ahead and try to solve it but suddenly start getting pushback from everywhere and eventually things don’t work out as you had thought they would. You are left bitter and frustrated at “them”.

How many of you have been in this situation? I know I have, and today I want to talk about what I have learned from those failures. This is an idealized version of how I now think about orchestrating high-impact changes. There are many “real-world” details that you will have to fill in based on yourself, your team, and your organization.

As an engineer, I have often had a somewhat reductive point of view of the organization’s problems. My mind jumps straight to what system can I build to solve a problem. This tech-centric perspective told me that those who couldn’t see that building this type of system will solve the problem just “didn’t get it”. Sometimes, I believed that even if I couldn’t convince “them” (my manager, my PdM, other engineers in my team, etc), I would do it my way and they would thank me later.

DON’T DO IT!

This is the single worst thing you can do in a team. Working in a team successfully implies having the ability to convince your team and stakeholders about why you see a problem a certain way and why you think a certain solution will work. The kind of behaviour I just spoke about is a direct refusal to engage with the system around you. If your team saw you doing this, you will never regain their trust because not only did you fail to convince them, you overrode their disagreement and did something for which they now share accountability.

I’ll share some systemic reasons why you are wrong to act like this in a minute. But there are practical reasons too for why the lone ranger act is unlikely to work. Software engineering is a team sport. Even if you go off and do something your own way, who will make your solution work on the ground? The people you did not convince? The manager you did not get buy-in from?

Good intentions versus Systems Thinking

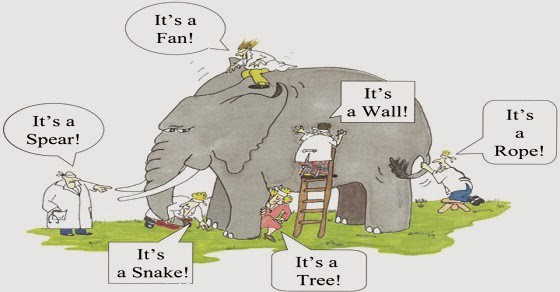

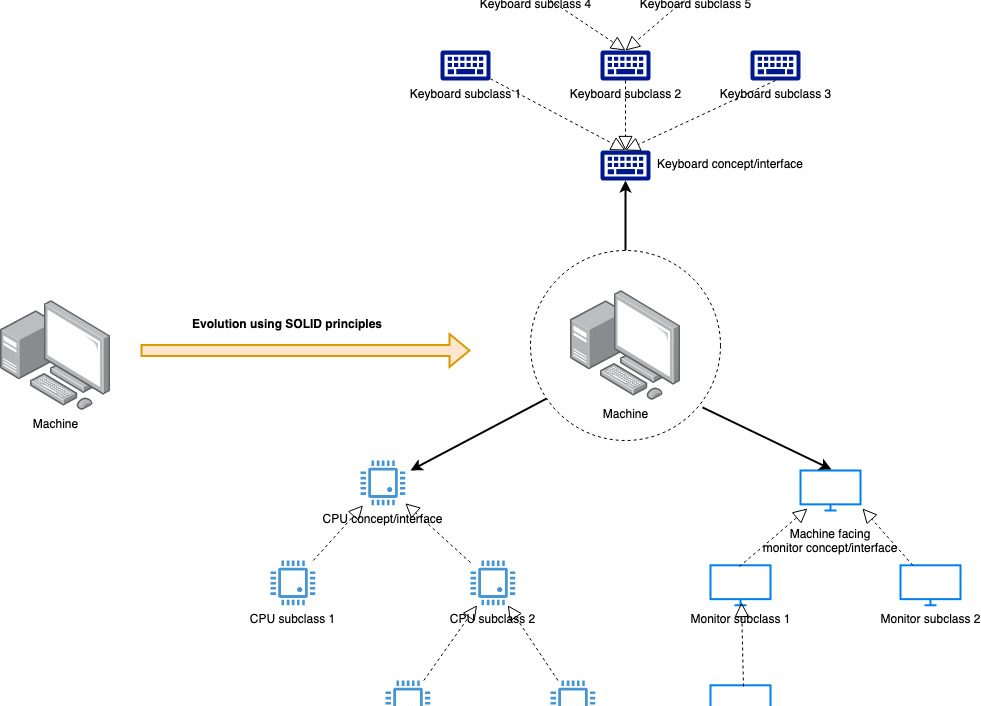

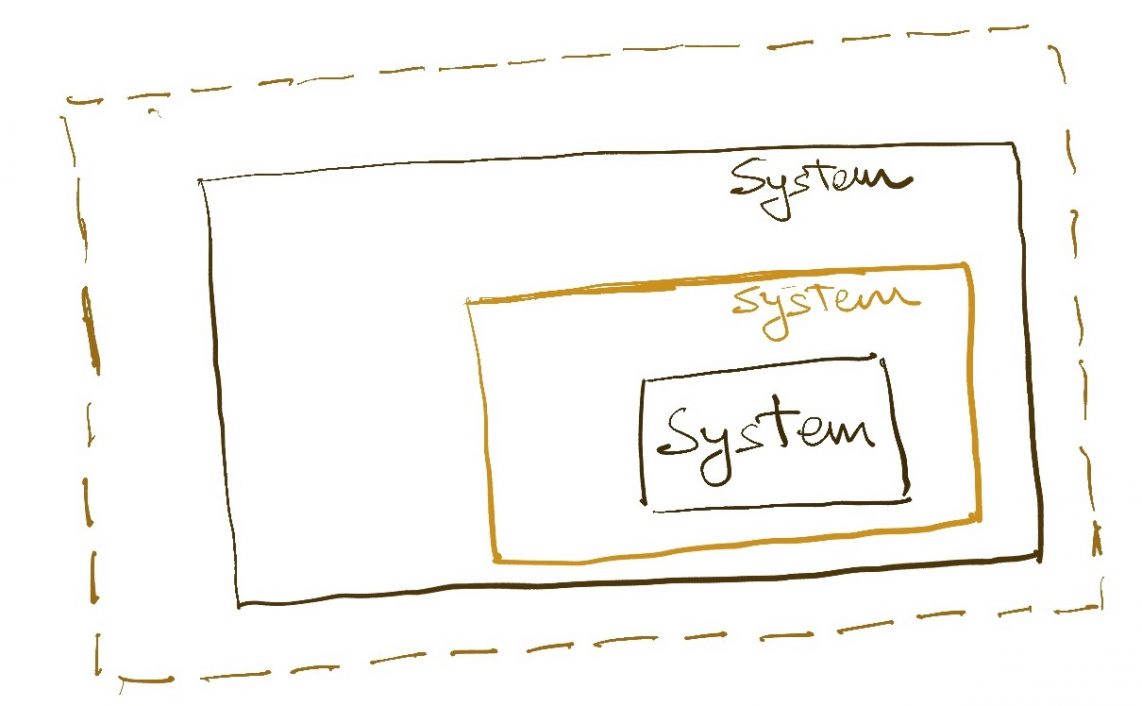

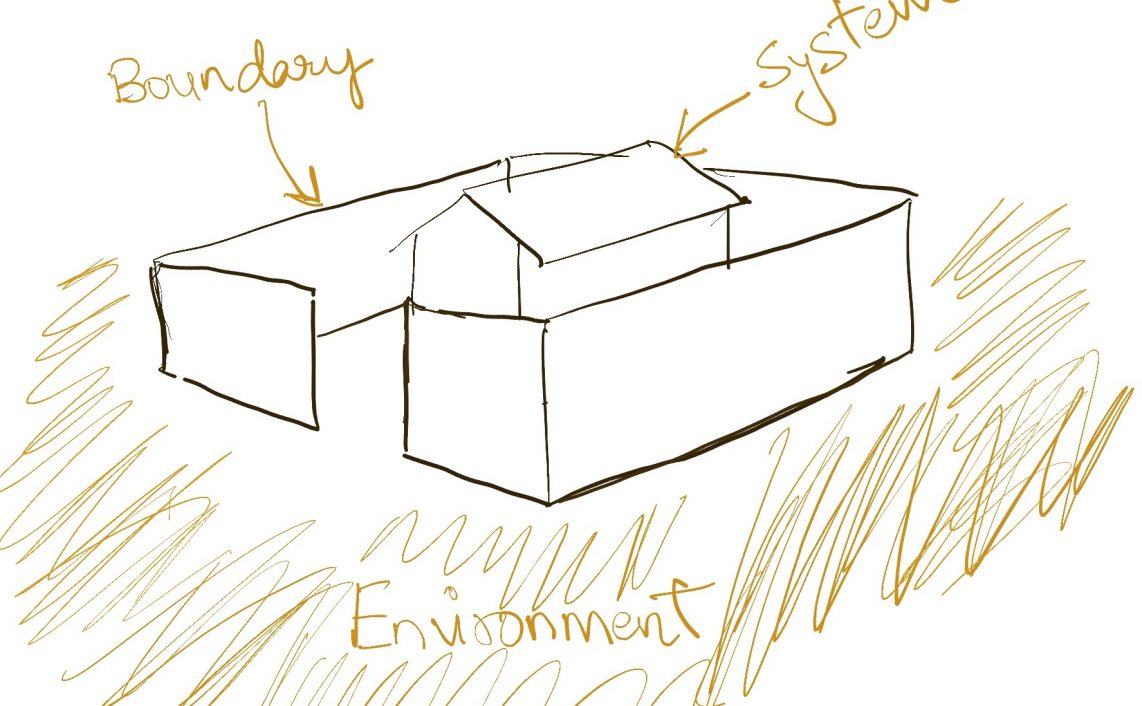

Systems thinking tells us that all actors in a system have different mental models of the system. Donella Meadows calls this “Bounded Rationality” in her book “Thinking in Systems“. Each actor has their own perspective, problems, and priorities. While the symptoms may be visible to everyone to some extent, their interpretation of underlying causes can vary wildly. This is one of the reasons “root cause analysis” is sometimes a fallacy – there may not be one root cause. Often, problems are caused by actors working on local information for local goals. Replace “actors” with departments or employees and you get a reasonable picture of how organizations work.

The solution, especially for large or complex problems, isn’t often an objective truth that can be shown to be true or correct regardless of perspective. If a solution involves multiple actors, we are trying to change the way all of them view and interact with their world. We can do this in a command-and-control way but this takes away the agency of the actors. No one likes to be told to do something “because I said so”. This can easily cause “Policy Resistance” – actors resisting or circumventing a central directive. Here’s a compilation of some of the most hilarious backfires of this model of working. This is what you are up against in trying to “get in and do it myself”.

Let’s think about the problem. Is it even a problem? It may be, but my particular framing of it reflects only my interpretation of the aspect of the problem that is visible to me. Perhaps whatever-it-is is only a problem as perceived from a technology standpoint (“we are no longer a tech company, what should we do”?). Unless I have exposure to all viewpoints and information (practically impossible in an organization), my understanding of the problem could be biased or incomplete. Someone from the business teams could have a completely different point of view on the same visible symptom. What’s ironic is that we could both be right!

The other problem is that this POV assumes that all solutions are technical and I am the centre of the world. This is obviously not correct. In most organizations, technology is only one part of the landscape and often a small one. Until we surrender our vantage and ego, we are unlikely to see the full shape of the world.

Build a shared context and worldview

If you want to build a ship, don’t drum up people to collect wood and don’t assign them tasks and work, but rather teach them to long for the endless immensity of the sea

-Antoine de Saint-Exupery

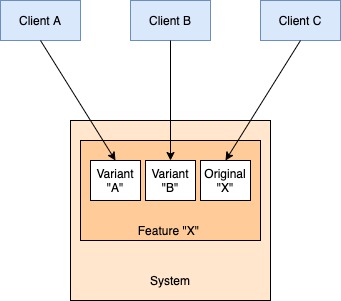

A better way of creating change is to look at the system collaboratively from multiple actors’ perspectives and build a shared understanding/context of what it looks like. This goes beyond convincing or getting buy-in on my perspective. Invite collaboration by getting all involved actors to come together and build a common world. This new, shared worldview will likely be far richer than any single actor’s view, and the process of constructing it will start a dialog where problems and solutions are easier to discover and discuss.

The problem, therefore, is not the problem. Building a shared view of the system – that is the problem.

In this process, my perspective can serve as the basis out of which the discussion grows. This suggestion is based on Tim Casasola’s suggestion of building containers for collaboration. We want a collective framing of the environment and the problem, but having a starting point helps.

Scoping the audience in these discussions is critical. The group should be as small as possible to cover all viewpoints needed. This process is about balance – not ivory tower, and not a committee. Every member of the group should be directly involved in the resulting decision or directly impacted by it. Anyone not directly impacted is a consultant who may inform the group but has no part to play in it. e.g. If the problem is “our systems have too many outages”, including marketing in the conversation has no purpose – keeping it limited to technology and operations should suffice.

From problem to solution

This is where I have made the most mistakes in my career. Even in situations where I and my team agreed on the problem, I used this agreement as a vindication of my original perspective and reverted to acting on my solution. It was “ah everyone agreed, so now let’s get to work now”.

The obvious problem here is that the shared context is abandoned and we go back to “Let me tell you what to do” mode. Given that a collective understanding exists, it is especially regressive for me to push my perspective all over again.

A far better way is to simply continue the dialog now in the direction of solutions. Very often, the process of building the shared context will reveal solutions (often multiple) organically. Essentially rinse repeat till the team converges on a solution. Of course, it can be that there is no single solution acceptable to everyone. We can use compromises, or multiple limited solutions, or continue to disagree forever. Any way we choose, the key thing is that everything from now on happens with a collective agreement.

The one thing we want to avoid is going rogue if the conclusion isn’t to our liking. As I started out by saying, “against the tide” efforts are unlikely to succeed and erode the team’s trust forever.

What should we do next?

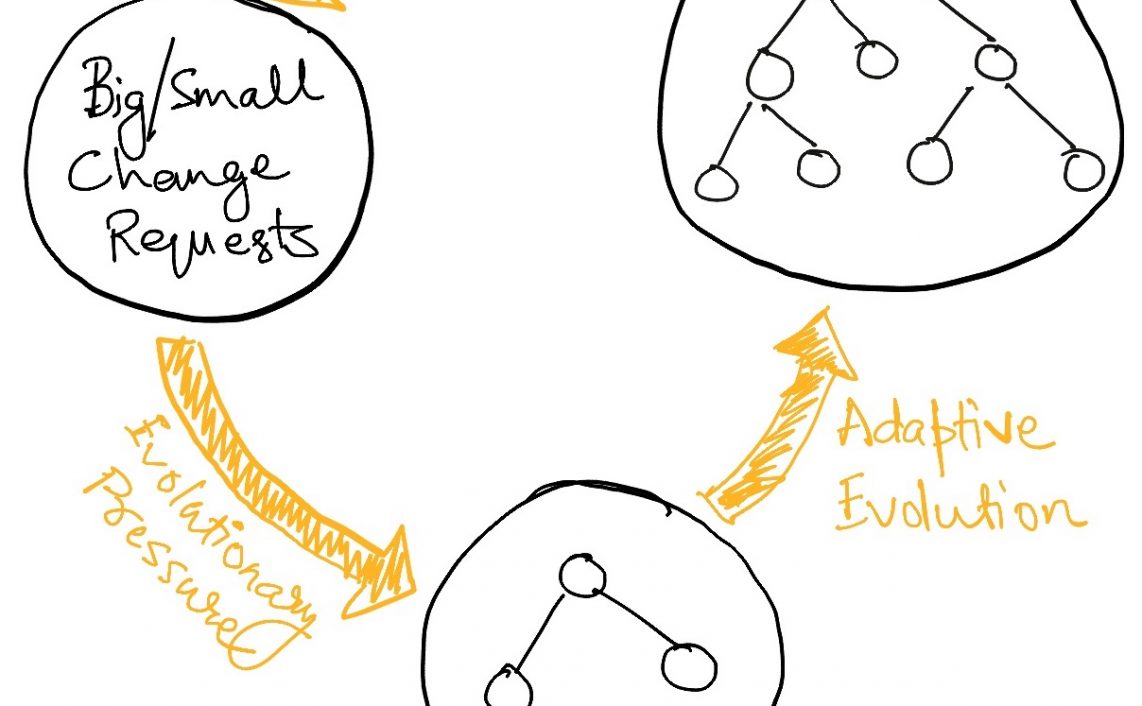

Nothing stands still, ever. A shared perspective is not a static thing. Every action we take changes the environment, so to maintain our situational awareness, we need to keep the dialog going. With the dialog constant, the worldview is constantly updated and new possibilities are constantly explored. The next steps become organic increments rather than big bang “quarterly plan” type efforts.

Since this shared understanding is the core of how a team functions, the context IS the team. If the worldview changes significantly, a whole new type of team may be required. In any case, the key is to keep talking and learning.

Why doesn’t it happen often?

This idealized process sounds good enough that you’d expect some variant of it to be attempted often enough.

- The process is not very efficient as a one-time activity to deal with some specific situation. As I said before, the dialog is a flywheel. If it isn’t kept alive, then you might as well not do it.

- It is extremely hard for intelligent people to surrender their POVs. Ironically, the more passionate each of them is about the problem, the harder it gets to contribute constructively to the collective.

- The idea of including “everyone involved” leads to involving so many people that building a shared context goes from being difficult to being impossible.

- Often, there are bad-faith actors or power-play situations. The participants are not even interested in the intent of the dialog – only in extracting some other types of outcome.

Read next: Reduce the need to collaborate by using good desgin

If you liked this, subscribe to my weekly newsletter It Depends to read about software engineering and technical leadership

Interesting read. Reminded me a little bit of Hashicorp’s model where they use written communication to define the problem and then agree the solution collectively.

https://works.hashicorp.com/articles/writing-practices-and-culture

Thanks for sharing this Duncan. Pretty interesting!